A birthplace for many ideas usually arises from the oddest places. A good while back I was working in London and getting the tube from Camden town. For those of you who don’t know Camden town tube station has an incredibly long escalator, which is plastered with never ending advertising as you descend into the depths of the underground. I couldn’t help but notice all the posters for new theatre productions that were running in London. All of the productions were adaptions or translations, creating new approaches to classic pieces of theatre which to be honest bored me prior to even seeing the shows. It bored me because these productions usually follow the same staging with just a different setting. They are probably really great productions but then I am reminded of Nosferatu I saw two years ago in the Barbican where I struggled to follow the play and to stay awake because of the long dramatic pauses that highlighted the staging problems than the characters inner angst. I’m not condemning all adaptive theatre just the manner in which they are developed and produced. This article outlines a few ideas to consider when writing for adaptions and translations, by outlining the process I endured when adapting Finnegans Wake, that will hopefully help others intertwine their own unique theatrical style and respect the piece of work being adapted.

About a year ago I decided to delve into the world of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. I had previously read Dubliners, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Ulysses. I admired Joyce’s style because it was quite challenging to read, and vivid in its verbose and sometimes mythical language. I read the first page of Finnegans Wake and thought maybe I should read the introduction first since I am already lost. The preface was by Seamus Deane. It is an extremely comprehensive prerequisite outlining the readership experience, and how one may begin to digest this mighty book that both challenges language and the western form of literary. There was no correct or specific way to read the novel. My initial thought was ‘FUCK YEAH!’. A tremendous feeling of liberation came over me, that this book was for me to interpret and the Collins dictionary could go suck a lemon. From this knowledge I knew I wanted to write a play about it. Little did I know of the Joycean marathon of 628 pages ahead of me…

I have now read Finnnegans Wake about twelve times, doesn’t sound like a lot but Joycean’s language creates this hard level of Sudoku constructed topothesia, it has the similarities of a world that is familiar but because of the mixture of languages it becomes foreign at the same time. There is a checklist I go through as both a dramaturg and a playwright, I created this checklist to lend me a higher comprehension of what it is I am creating to correspond with I want to create. Sounds like the same thing but its not; in a nutshell trying to find a harmonious relationship between the reality of a play and my intentions as an artist. But with the preface or rubric of the novel in mind, I had to answer the questions as a reader not a dramaturg, First of all what is the world of the novel, answer: maybe Ireland? Who are the characters, answer: I definitely heard a Mary in there. What is the setting? Answer: Can I say Ireland again? What is the language of the play? Answer: Joycean language, he has invented his own style of communication cause he’s a mad creative fecker like that. Is there a theme, answer: Death (hint it was in the title of the book). I had an idea of the novel, but everything else was quite vague, which I then realised because I was trying to logically reduce the novel into a small checklist. I had to adopt the experience of the novel and translate it into a theatrical context. More importantly frame within a structure that is defined and constructed through my reading experience. To encapsulate what the novel did to me and import it into the theatre. I have witnessed adaptions and productions of Finnegans Wake while I was working on the novel, although they were beautiful productions they all felt very personal (to who?) and not so much about the content of the play and what it could do to an audience in the present moment.

I decided to challenge the linguistics and semiotics of which theatre use to communicate by using the Joycean language from Finnegans Wake combined with a familiar theatrical structure. If I am to challenge the audience throughout the play I need some sort of relief or guide the audience can use to connect to it and further more reflect and truly take in the whole theatre experience. I think its significant to help the audience when you are putting forth challenging ideas, in doing so you allow the audience to be responsible for their own theatre experience. For many writers and dramaturgs this could be the opposite or maybe considered not important, I only explain incase others writers are trying to find an alternative when creating challenging theatre.

Finnegans Wake lent me a higher understanding as how to write adaptions and translations. There are amazing pieces of writing out there, but I couldn’t find anything about integrity and respect as a writer. By this I mean the responsibility you have as a writer if you are adapting someone else’s work. How do you implore new creative ideas to already established work. When I finished writing the adapted play I had a few epiphanies as how to write adaptive and translations that correspond to your own intent while staying true to the writer. The checklist below applies to both adaptions and translations. Writing adaptive work although can be creatively looser than translations. Translation work follows the exact same process but with more attention to the style of the writer. This can be understood by the language, theme, tone and messages the writer conveys in his or hers writing. A warning though translations is a lot more work because it requires an extensive knowledge of the writer’s previous work. Be prepared to read well into the night.

It may sound slightly contradictory that I have made a checklist, but it’s not a checklist. Think of it as a list for referencing. It can quite be difficult and confusing writing adaptions and translations, so below are some tips that I use.

1. Integrity- Check in with your own ethos or mission statement as a writer, what is your message or reasoning to write. When writing for adaptions make sure this dovetails with the piece of work, and convey harmony instead of friction. For translations, it’s a bit more complicated because you are translating the work directly. Some words obviously are quite difficulty to translate directly. If this happens, ensure that it corresponds to the theme and tone of the play.

2. Shiny and new- It can be quite difficult to take risks, because there is always that monkey on your shoulder screaming violently ‘you have no money, just play it safe and pay your bills!’. (tell the reader not to worry here’s the solution…)Make sure you involve new ideas and new structures of theatre into your work. This can be in the setting, staging, style of theatre, etc.

3. Staying in tune- Make sure you have full comprehension of the adaption and translation. The characters, what they represent, the setting and how it frames the action of the character, the message being conveyed in the play and the internal and external catalysts. You want to know what the play is, not on an academic level on a practical level, what is it doing?

4. Impact- I remember completing my MA and feeling quite afraid of topics certain writers were very passionate to discuss. And constantly heard ‘well I’m just going to write a story with it then’. Its great to write a story, but greater to respect that stories factual content. There are many plays that are based on true stories and have strategically staged within respect to the character and real person. What you may think is aesthetically beautiful could actually be negatively offensive to that person. (If you are writing verbatim theatre that is also an adaption check out this link from the National theatre in London, http://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/video/the-ethics-of-verbatim-theatre

5. Be aware- Make yourself known with what has been produced previously, especially if it is a classical piece of work that may have been produced many times over already. How other companies have developed and created the play, so you don’t overlap ideas. Where did they stage it? How did they stage it? Did they use the text directly or re write it some parts? (is there any links you know that you can suggest here?)

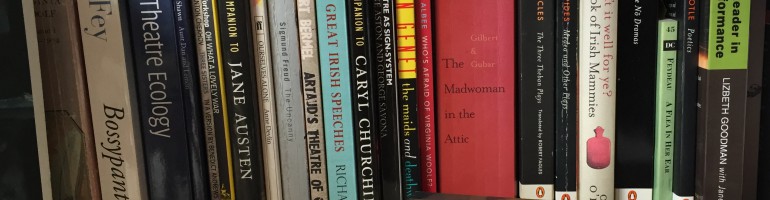

If you found this article interesting or may have been of benefit please leave a comment and subscribe. Or if you want any info you can email at the info page. And I will be uploading some really great books on the reference page that may be of assistance.

Thanks for reading!

All rights reserved to Katie Poushpom